"Time creates images the eye can't see." Bill Wittliff

Bill Wittliff's accomplishments in the fields of art, literature and film making are truly breathtaking. Based in Austin, Texas, he has had a distinguished career as photographer, film producer, director, publisher and screenwriter of the Emmy award-winning television series Lonesome Dove, and the films The Black Stallion, Raggedy Man, Barbarosa, Country, Legends of the Fall and The Perfect Storm. Classic Wittliff photographs made on the set of Lonesome Dove will be exhibited at Andrew Smith Gallery, along with a selection from La Vida Brinca.

As a photographer Wittliff has long been known for his photographs made on the set of the 1989 TV mini-series, Lonesome Dove. In the late 1980s, Wittliff, who had already written scripts for the westerns Barbarosa (1982) and Red Headed Stranger (1986), was signed to write the teleplay for Lonesome Dove and serve as its Executive Producer. Wittliff photographed the cast as filming began in March 1988 in Austin, Texas, making memorable photographs of Robert Duvall, Tommy Lee Jones, Robert Urich, Danny Glover, Anjelica Huston, and Diane Lane in their various roles. During the 88 days of filming he photographed the cast as they filmed in Del Rio, Texas in April, and Santa Fe, New Mexico in May. Aired on CBS in February 1989, Lonesome Dove's high ratings and critical acclaim quickly made it a timeless classic among fans of the American West. One of Wittliff's photographs from the series titled Gus on the Porch remains the best selling single original photograph of the last decade.

Wittliff's photographic relationship with Mexico began in 1969 when he made numerous trips to the vast El Rancho Tule in northern Mexico to photograph the vanishing culture of Mexican vaqueros as they worked cattle and horses. He continues to divide his time between Texas and Mexico and is intimately familiar with the history, culture, geography and spiritual beliefs on both sides of the border. Since the late 1990s Wittliff has been photographing Hispanic fiestas, religious observances, people, architecture, and rural scenes in Mexico, Texas, and New Mexico. Far from being documentary, these photographs probe beneath the literal look of things, exposing an uncanny realm where half ordinary, half specter-like forms inhabit another reality. Over 100 photographs appear in Wittliff's recent book, La Vida Brinca (Life Jumps), published by UT Press in 2005.

These days Wittliff shoots with pinhole cameras, all of which he has made himself. Essentially, pinhole photography is made without a lens. Light simply passes through a hole in a camera to form an image on film. Wittliff refers to his pinhole cameras as "tragaluz," or "light swallowers." While a pinhole camera is capable of producing images with no distortion, great depth of field and reasonable degree of resolution, it requires longer exposures than conventional cameras. Wittliff achieves soft-focused effects by controlling the size of the pinhole camera's aperture, the distance to the film and the length of the exposure. Thus, in the fraction of a second or even a few minutes it takes to make a pinhole photograph the ordinary world is jolted out of its familiar shape. In making photographs Wittliff is open to things he can't control. "It's not just you creating the image," he has said. "You are part of the process, but another part of the process is that you just have to make yourself available for what might appear before your eyes." "Happy accidents" continually contribute to Wittliff's photographs and give them their unique power. These unpredictable effects, like the spontaneous flares of shadow and light characteristic of pinhole images "elevate the scene from one of simple revelry to awesome revelation."

Dreams of Tenochtitlan (Sueños de Tenochtitlán), Mexico, 2000

Aztec dancers whirl in a fiesta, their capes and feathered headdresses blurred by the camera's exposure. Their passionate dance seems to invoke the dark clouds swirling above the spiked towers of the plaza's cathedral.

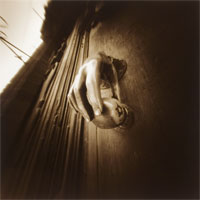

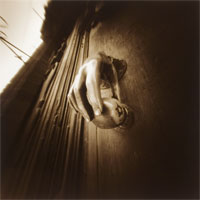

To Fly (Volar), Mexico, 2000

The ordinary rules of gravity and physics don't always apply in Wittliff's photographs. A clothed figure, wildly out of focus, plunges down through the air above the suggestion of rooftops and trees. There is no rational explanation for this image, which simply invites viewers to accept that inexplicable things can and do happen.

Meteor Storm (Caída de Meteoros), Texas, 1999

Poles with crossbars and ropes appear fuzzily, as if seen though a blotchy window. Much is obscured, but the impression is of a clipper ship with furled sails, ropes blowing in the wind and waves heaving in the background. The photograph (actually a close-up of a tiny ship in a bottle) connotes for Wittliff the arrival of the Spanish in America, a time as deadly its own way as that Perfect Storm he wrote a screenplay about.

My Town (Mi Pueblo), Mexico, 1998

Encircled in dark tones, this timeless Mexican street scene focuses on a man in a sombrero who sits on a curb between a horse and a cart. The horse faces the camera, its head massively enlarged by the camera angle. In the distance a palm tree and statue are silhouetted against a radiant white sky.

The Girl in the Mask (La Chica Enmascarada) Mexico, 2003

Wittliff captures the macabre side of fiesta in this photograph taken at close range of a person wearing a white mask, dress, and carrying an umbrella. For all her graceful, feminine trappings there is something slightly disturbing in the languid eyes and half smile of this beguiling, masked creature.

Life Jumps (La Vida Brinca), Mexico, 2002

If Manuel Alvarez Bravo and Marc Chagall had collaborated on an image they might have come up with something like this photograph. Pedestrians walking down a road in a Mexican city during the Easter holiday are dwarfed by giant paper mache figures called Judases who float serenely overhead. But in this delightfully wicked event the Judases, made to look like reviled cultural or personal figures such as presidents, bosses, or ex-spouses, are designed explode in all directions.

To Knock (Llamar), Mexico, 1999

On an empty Mexican street Wittliff photographed a polished brass door knocker shaped like a woman's hand holding a pepper, and molded with utmost sensitivity. Illuminated by the pool of light in the center of the photograph the hand, complete with articulated fingernails, glistens like quicksilver.

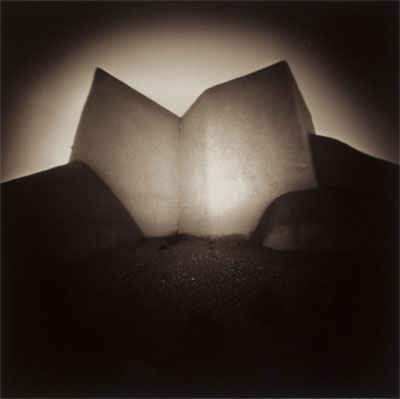

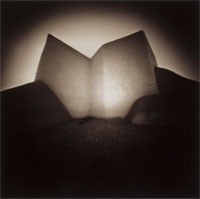

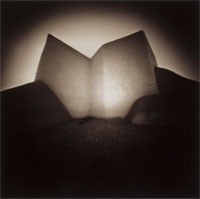

The Church (La Iglesia), New Mexico, 2005

The famous Rancho de Taos church has been painted or photographed by nearly every well known artist who ever visited northern New Mexico. In Wittliff's photograph the familiar church is, for once, unfamiliar. The main structure of the building emanates light, in contrast to the dark buttresses on either side. Arching over the church a halo of light bleeds into with velvety blacks at the top edges of the photograph. The highly abstract church resembles nothing so much as a monumental, open book on whose pages nothing is written.

Bill Wittliff was born in 1940 in Taft, a small town in south Texas. In 1963, after graduating from the University of Texas, Wittliff and his wife Sally, founded the Encino Press, which specialized in nonfiction about Texas. Among their publications was Larry McMurtry's seminal book of Texas essays titled, In a Narrow Grave: Essays on Texas.. Wittliff's interest in Texas literature and historic photography led he and his wife to found the Southwestern Writers Collection and Wittliff Gallery of Southwestern and Mexican Photography at Texas State University. He also gathered an extensive collection of photographs from the commercial photographers who worked Boystown in Nuevo Laredo. Despite his successes in Hollywood, Wittliff chose to stay in Texas where he continues to support and influence its arts and culture.

Bill Wittliff's photographs have been exhibited in numerous galleries and institutions throughout the U.S., Mexico and Japan, including the Institute of Texan Cultures, the National Cowboy Hall of Fame, the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, and the Texas capitol. He has two books of his photographs in print: Vaquero: Genesis of the Texas Cowboy (UT Press, 2004), and La Vida Brinca (Life Jumps) (UT Press, 2005).

Liz Kay

|