Duwawisioma (Victor Masayesva Jr.):

Màatakuyma

November 30, 2023 – January 27, 2024Extended to March 23, 2024

"Màatakuyma,

—Now it is becoming clearer to me."

— Duwawisioma

|

|

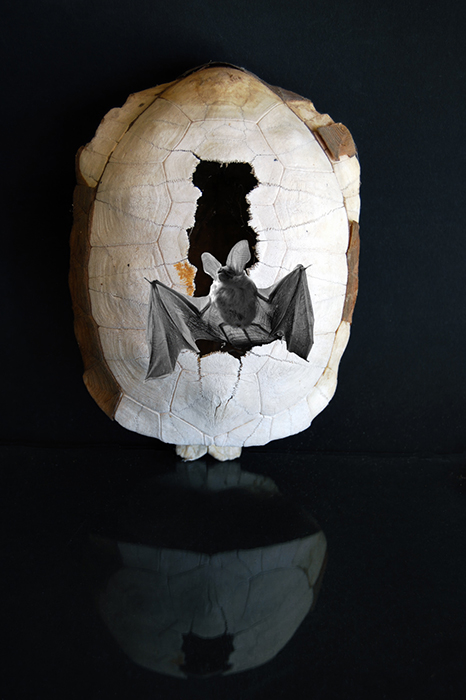

©Duwawisioma Kiva I & Kiva II, 2023. A turtle shell, the earth, a kiva from which emerge the negative (bat) and the positive (larkspur), toxic and healing.

Andrew Smith Gallery Arizona LLC. is pleased to announce the exhibition Màatakuyma by legendary Hopi photographer and filmmaker Duwawisioma (Victor Masayesva Jr.). Duwawisioma (b. 1951) continues a lifelong quest to understand "existence" and "being" in terms of Hopi ancestral traditions in the modern world. In this exhibition he focuses on the ontological ideas engendered in the Hopi lunar agricultural cycle, combining cosmology, the emergence of the Hopi, animating the personalities of place, and elements of nature, death that leads to regeneration, and cycles of creation and destruction.

Time is not linear in Duwawisioma’s world--ancestral time is a vortex, a whirlwind that underpins and mixes with modernity-- cars, casinos, electronic communication, photography, and filmmaking are a constant threat to ancestral time to be embraced and opposed and ultimately to be harmonized with.

The people of Duwawisioma’s home village of Hotevilla, Arizona have a long tradition of rebelling against government, whether opposing the colonizing American government or the traditional Oraibi government, whom they separated from in 1906. They fought against the 19th and 20th century "Indian schools" and have imposed restrictions on visitors to the village to diminish the exploitation from cultural tourism. Duwawisioma has also long advocated against museum practices which highlight sacred artifacts, a practice that has historically led to the looting of these sovereign items.

Hopi sovereignty and identity are central to Duwawisioma’s life and he reminds us that the local is universal, respecting and revering that which sustains us: corn, crops, water, winds, the land. The harmonious path is to be aligned with nature in the ways laid out in ancestral traditions.

Duwawisioma grew up in Hotevilla on Hopi Third Mesa. He attended the Horace Mann School in New York City in his teens and then studied English literature and photography at Princeton University. Outside of his schooling he has always lived in Hotevilla, where he has worked with the community youth and elders to record Hopi cultural history and has worked in many other capacities in the civic life of the Hopi and the religious life of his clan and community. Since 1981 he has been making groundbreaking movies and videos such as Hoplit (1982)and Itam Hakim Hoplit (1984)made in the Hopi language and selected for the National Film Archives in 2023, as well as receiving the Gold Hugo at Chicago International Film Festival in 1984, Ritual Clowns (1988) receiving the American Film Institute’s Maya Deren Award, Imagining Indians (1992),and Paatuwaqatsi - Water, Land and Life (2007). During the last 32 years, the Andrew Smith Gallery has hosted half a dozen exhibitions of Duwawisioma's work: Recent Works (1991), Victor Masayesva Jr. (1993), Tumuola (1996), Nuclear Reservations (1998) and Drought (2006).

The Hopis' survival has always depended on prayers for favorable weather conditions. For thousands of years Hisat Sinom and later the Hopi have inhabited a region of high, arid mesas where there is little rainfall. No rivers or streams flow through the territory, though a few permanent springs provide the people with drinking water. Over time, the Hopi developed their own farming systems and crops particularly suited to their specific environment. Integral to this is the respect and reverence for nature and its elements and the ceremonies that encompass these relationships. Duwawisioma’s images describe the animated and difficult relationships man has with the natural world. Relationships with places of emergence and spirits, the personalities of various elements of nature, germination and the destructive freeze, all must be considered; along with the personalities of specific places, such as places where there might be salt, water with the resident snake or the sacred Sipapuni in the Grand Canyon from where the Hopi emerged.

Natwani

The exhibition includes the 12-print narrative Natwani. This series imagines the Hopi lunar agricultural calendar: when there has been moisture, the timing and planting and harvesting of corn and other crops, the skill of the farmer, and the elements of weather mixed in with a cycle of social activities, marriage, and ceremonial activities.

Corn is the dietary and spiritual base of Hopi life, and a skilled farmer understands this through the activities and rituals associated with the Hopi lunar calendar. The lunar cycles begin with moisture, then cleansing and then there are cycles of wind, planting, and harvest. Nature can be generous and beneficial providing germination, new life, and growth but it can also cause drought.

©Duwawisioma. Tsotima, 2016. #1 from Natwani.

Beginning about the time of the winter solstice the first moon encourages moisture to become snow in the dry winter air in order to have good crops. This is also the time for social dancing for the unmarried to celebrate community.

©Duwawisioma. Paaisau, 2023. #2 from Natwani.

Within this lunar cycle is the hope for heavy winter snow, saturating the land with moisture.

©Duwawisioma. Kyaarom, 2012. #3 from Natwani.

This macaw bouquet heralds the third lunar cycle Kyaarom, katsina season, the night dances, and the whistling wind.

©Duwawisioma. Naasavek, 2023. #4 from Natwani.

In the fourth lunar cycle the wind and weather is often extreme and critical decisions about the planting time of the corn and other crops have to be determined. The hope is for the cessation of the cutting wind.

In his 1998 series Nuclear Reservations he used this with the narrative title Ground Zero "a submerged atoll, an atomic test," suggesting an apocalyptic nuclear destruction. Here this scene heralds a new warning, that of climate change.

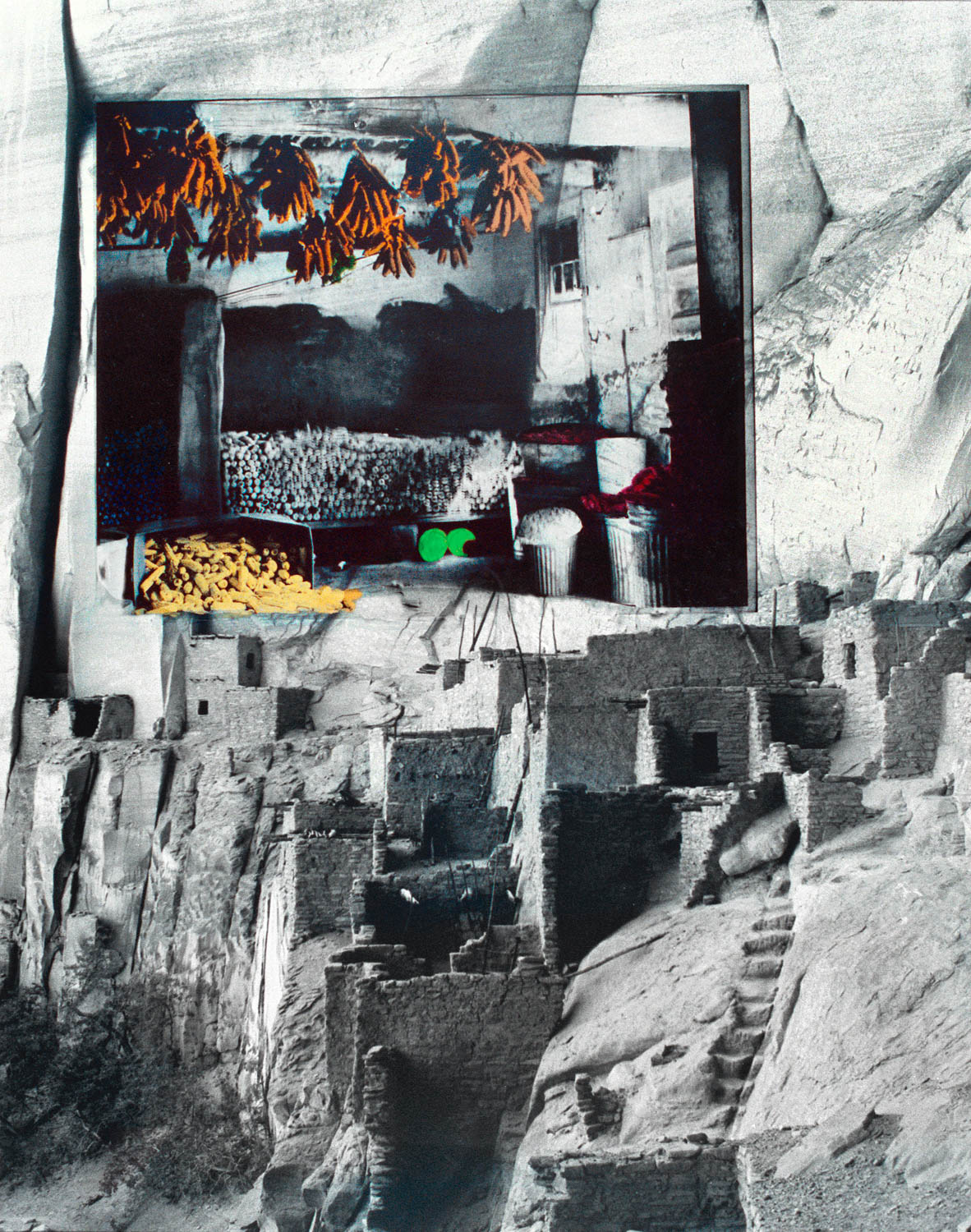

©Duwawisioma. Kawestima, 1981/2023. #5 from Natwani.

Kawestima has a sense of foreboding; is it time to plant or to wait. This image shows Kawestima, one of the ancestral homes of the Hopi where food was stored and in this lunar cycle is waiting to be moved.

In 1982 Duwawisioma photographed the ruins of Keet Seel, about sixty miles from Hopi. The ruins figure importantly in the clan's sense of their past and their future. For the present, they must acknowledge that the site has been transformed into a national monument by the park service. One of Keet Seel's great mysteries is contained in a legend that before the village was abandoned its inhabitants sealed up their well-stocked graineries. It is believed the nourishing stores will be reclaimed by those who return to Keet Seel. In his image, Duwawisioma superimposed an acetate sheet depicting pumpkins, corn, and herbs onto Kawestima.

©Duwawisioma. Muy’ing Tuu’oyi, 2006. #6 from Natwani.

This corn stack is the seed stock for crops and this cycle indicates the time for the big planting. This image was used in his 2006 series Drought, Duwawisioma noted that the Hopi word Tuu’oyi describes a stack or stash of corn.

In this image Duwawisioma is visualizing a powerful spirit named Muyingwa who controls the seed stock. According to an old story, long ago the Hopi village of Oraibi was facing starvation because Muyingwa had withdrawn the seed stock. Hummingbird found it underground where Muyingwa had hidden it and later it was returned to the people. In Masayesva's image Muyingwa lies on top of an arrangement of corn, feathers, and cat claws. In this year of drought, he is actually pushing the stash into the sand, withdrawing his seed stock underground, reserving it for another time. Perhaps he will return it next year.

The lunar cycle repeats and can be viewed as a 12-month cycle or two 6-month cycles.

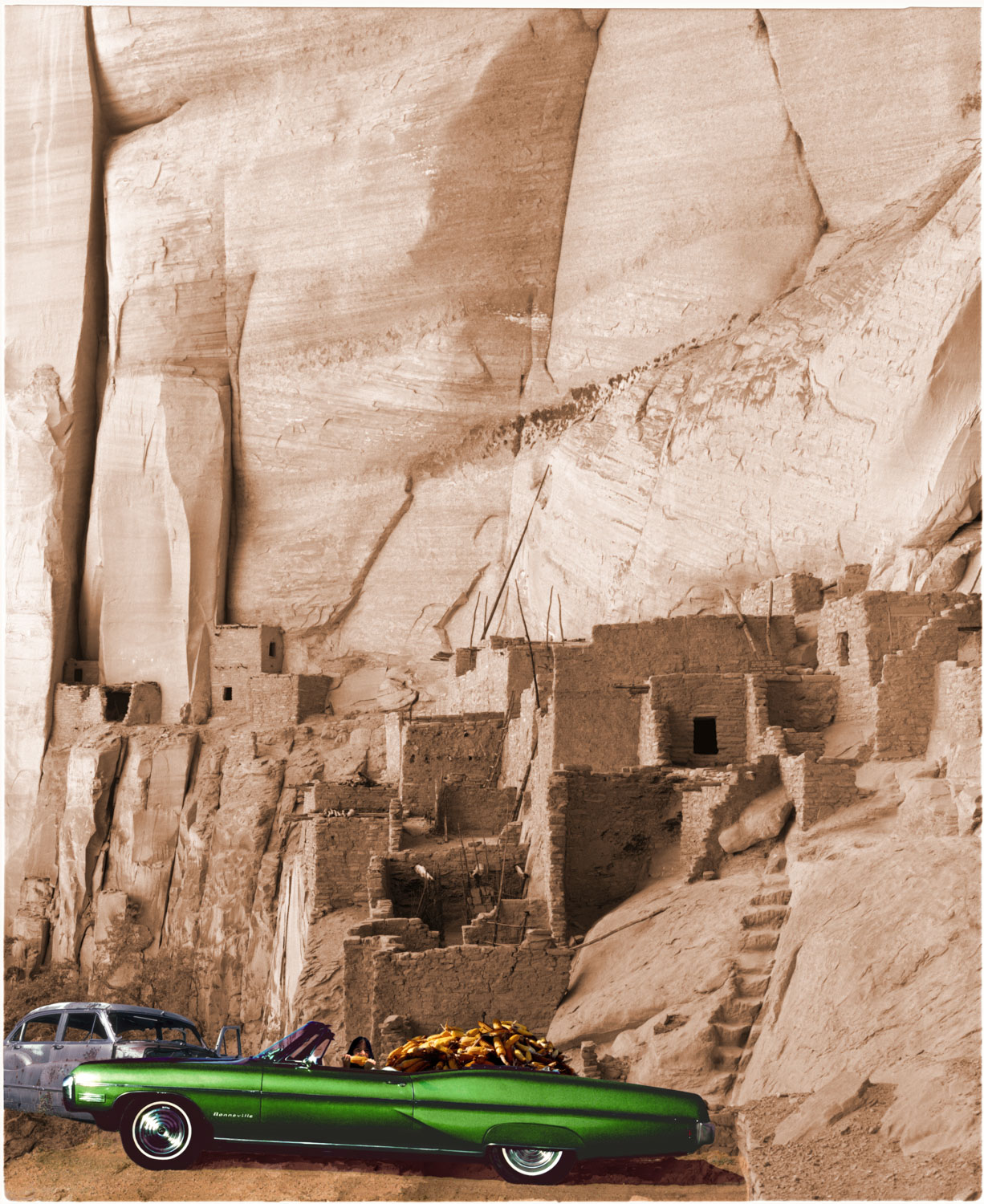

©Duwawisioma. Tupepta, 1997. #7 from Natwani.

Originally titled Green Mobile the car is filled with early green corn. The setting here is again the ruins of Keet Seel. In his book Husk of Time Duwawisioma writes: "Placing the green automobile (and the wreck in the yard) below the ancestral ruins at Kawestoma asserts that we still live here at Kawestoma. The seemingly empty, uninhabited ruins are in fact anticipating our return. They are waiting for us when we return by foot, car, wind, cloud, rain, or memory. This is my tribute to the ancestors who have gone before and who await us, looking for the swirling dust that signifies our transport—time."

©Duwawisioma. Palhik, 2023. #8 from Natwani.

In this cycle there is social dancing and harvest dancing, girls picking partners, the end of katsina season, and the hope for good and heavy rains.

©Duwawisioma.Tipongyaveh, 2023. #9 from Natwani.

This ninth cycle in the annual lunar agricultural cycle or a repeat of the third cycle, it is an uncertain time, hoping for the success of the crops. In this image Duwawisioma created a village made of slides set in a cornfield. The dance center or plaza is featured, where the women perform their dance, celebrating abundance.

©Duwawisioma. Mö'öngtotsi, 1986. #10 from Natwani.

This is the month for traditional Hopi weddings.

©Duwawisioma. Kwingyaw, 1998. #11 from Natwani.

Kwingyaw is a time of the frigid, cold north wind. It is the month for tribal initiations.

This image was first used in the context of Duwawisioma’s 1998 exhibition Nuclear Reservations where it was titled Cold Moon "cold arctic darkness, animals and humans moving out and south."

©Duwawisioma. Ninma, 2023. #12 from Natwani.

In this the final month of the lunar agricultural cycle the year is complete, At the winter solstice, offerings are delivered for all living things and the start of a positive new year.

Tuuviki

In the series Tuuviki (mask), Duwawisioma creates images intimating and sketching the personalities and presences that he imagined whether in the Grand Canyon or in a drop of rain. This follows the tradition of katsina representation that emerged from the Hopi migrations. Encountering special places, events, spirits, as well as environmental deprivations (drought, famine, etc.), these circumstances were encapsulated in the katsina and welcomed into the community.

©Duwawisioma. Pötavi, 2023 (from Tuuviki) #1

The spirit trail leads to Sipapuni, and the cyclical return to the place of emergence.

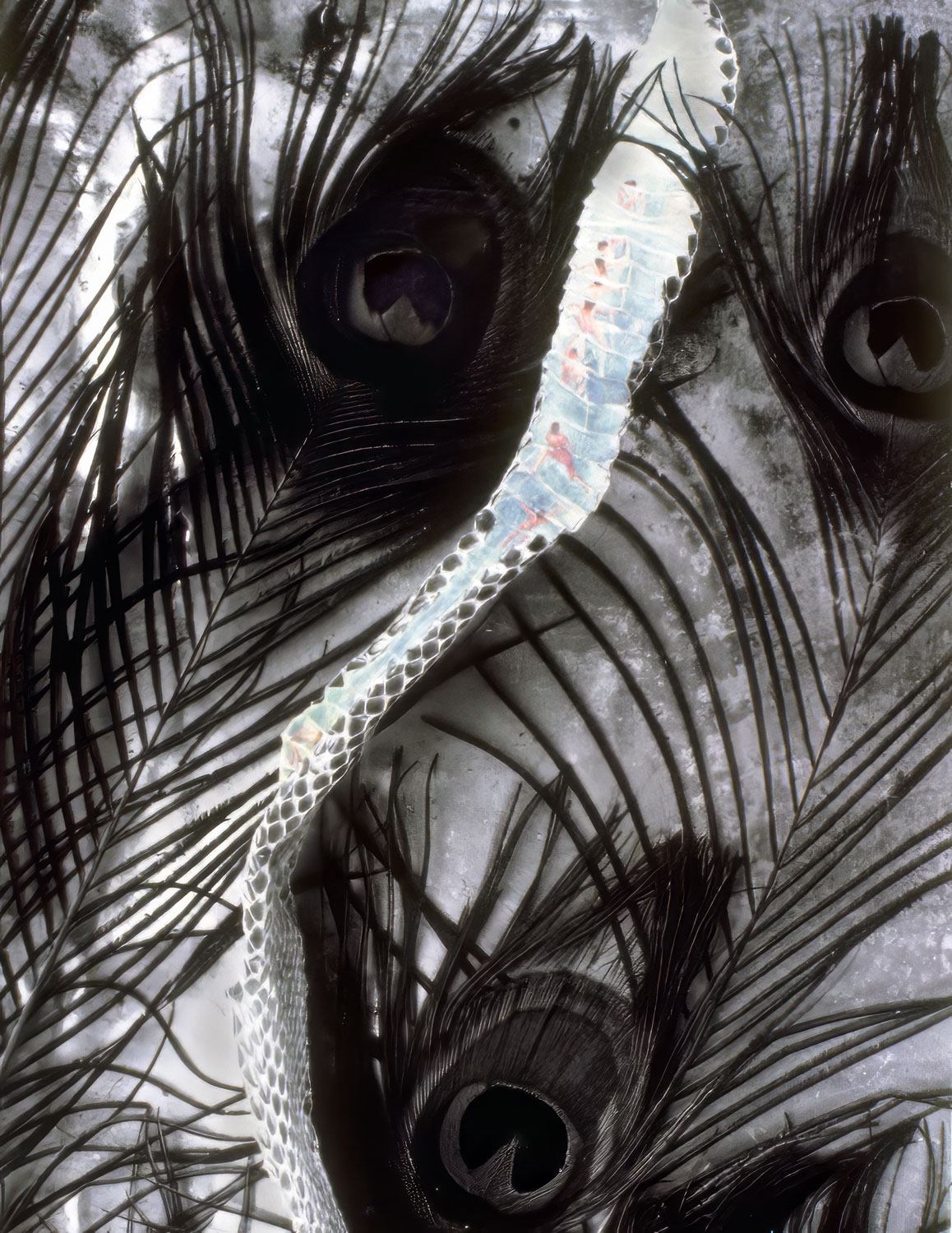

©Duwawisioma. Öngtupga, 1990/2023. #2 from Tuuviki.

Öngtupga (The Grand Canyon) The katsinas can represent natural forces in their masks, snow, or wind.

In a 1991 exhibition with a hand painted version of this we wrote: "Grand Canyon Salt Trail (1990) refers to an ancient pilgrimage to a salt deposit in what is now known as the Grand Canyon. This salt deposit was near a sacred place of emergence and the tortuous trail demanded great physical and mental endurance. How arduous the trip was depended on the persons making it." In Masayesva's image, the tiny men traveling through a snakeskin are contained within a giant mask that watches over the whole proceeding.

©Duwawisioma. Koyemsi, 1996. #3 from Tuuviki.

Koyemsi – Mud head, mud corn.

©Duwawisioma. Nanavöga, 1996. #4 from Tuuviki.

First presented in the 1996 exhibition Tumoala (Cat Claws), we wrote: "Of all Masayesva's images Nanavehya contains the biggest kachina of all. The bridge leading inescapably into the dark mouth of a casino implies that Native Americans (and the rest of the world, for that matter) are being sucked into a new manifestation of one of the oldest temptations; the lure of fast money. One eye of the kachina is a reel of film, the other is a gold slot machine. Not only money lures us into the casinos, Masayesva is saying, though a river of it flows below the bridge, but also the desire for fame and stardom. The cat claws are now hooked firmly pine boughs that are no longer the seeding place for clouds and rain but for money. Through Masayesva's vision the gambling kachina is also a great incinerator, transforming human resources into flame and smoke."

Duwawisioma still considers this risky spirit to be the gambler that everyone encounters.

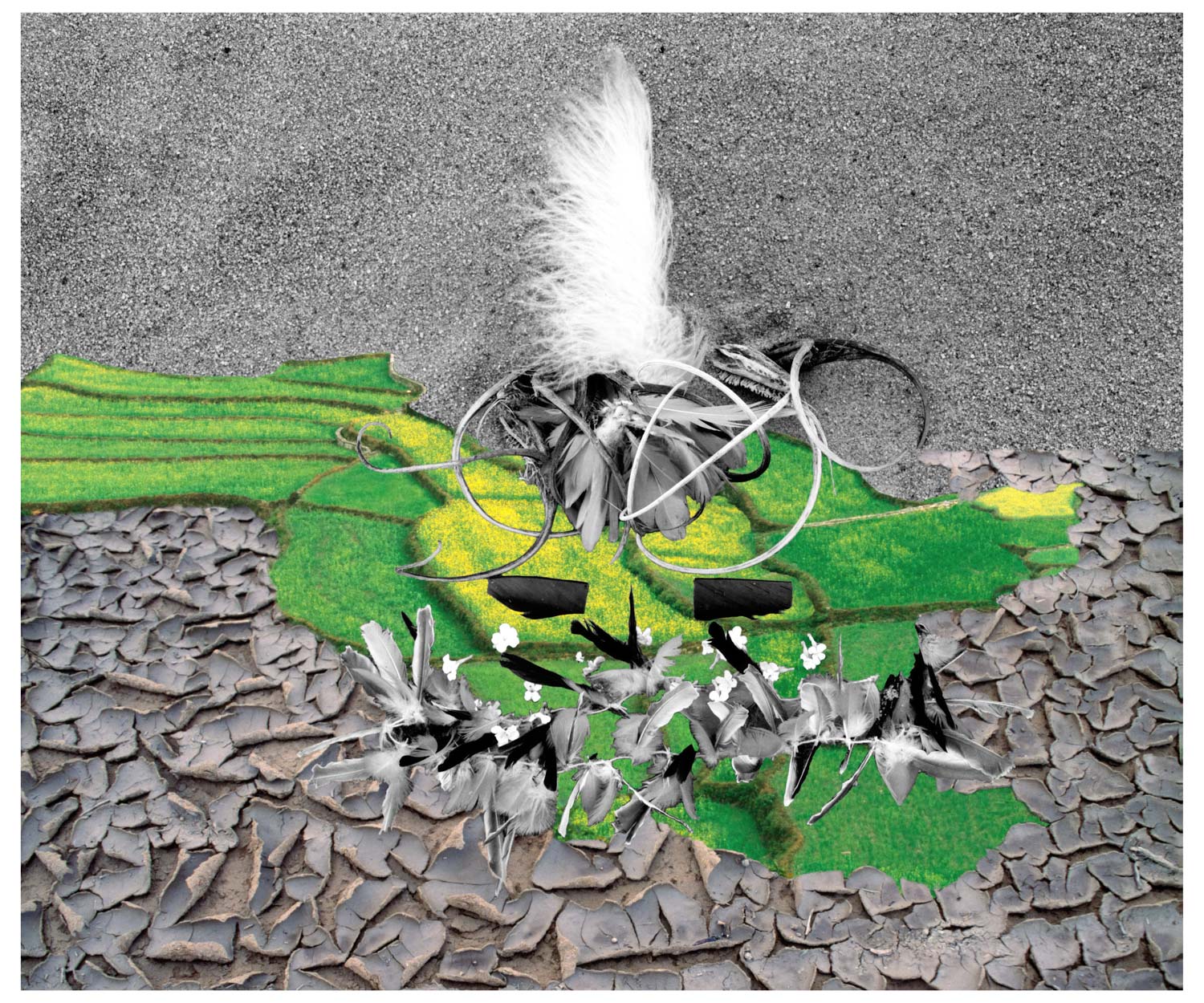

©Duwawisioma. Paamotoro, 2006. #5 from Tuuviki.

Paamotoro when rain hits the ground and splashes up, the personality of the raindrop emerges. In the 2006 exhibition we wrote: "The summer rain dances in Hopi center around kachinas. Kachinas represent the natural world within the Hopi culture. In this photograph feathers and cat claws hover over a green terraced mustard field. Leaves, flowers and feathers intertwine below two dark shapes that can also be viewed as the eyes of the Maiden Kachina."

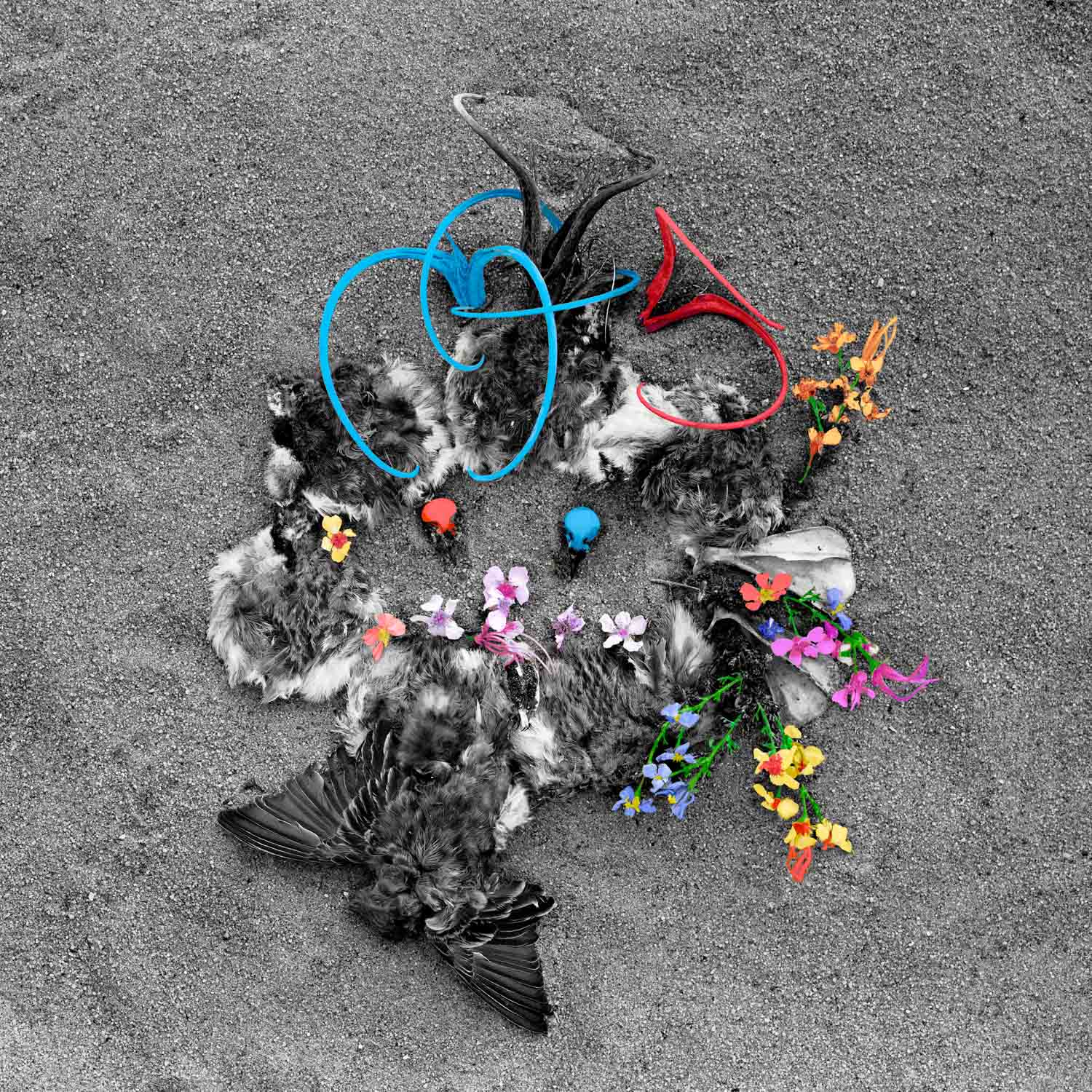

©Duwawisioma. Qoti, 2006. #6 from Tuuviki.

Qoti - from drought comes plenty, including tumbleweeds. In the 2006 exhibition Drought this image was titled Bird Flowers, Spring and we wrote of it: "The spring of 2005 was an unusually wet year in Hopi. Recalling the quality of that time, Masayesva made a black and white photograph of cat claws atop a wreathe of bird feathers, shells, and flowers resting on sand. To describe the delightful fertility of a wet season he playfully colored certain parts of the photograph. The cat claws, shells and flowers described in festive turquoise, red, orange, green, pink and lavender seem to jump out of the dry, bare ground."

©Duwawisioma. Duwapenvu 2023. #7 from Tuuviki.

Duwapenvu a mask of shadows and negatives, projected into the sand.

Duwawisioma is a groundbreaking artist using modern materials, film, negatives, digital amalgams, mechanical and electronic devices with ancestral imagery confounding Indian art critics as being too modern and Modern Art critics as being too Indian.

|

|

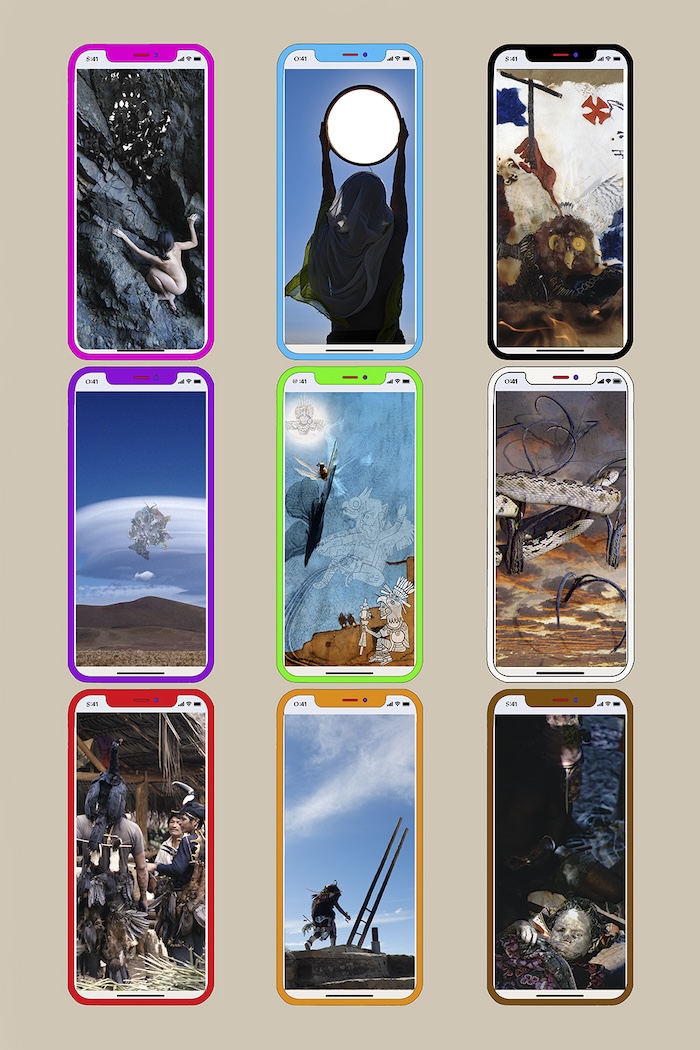

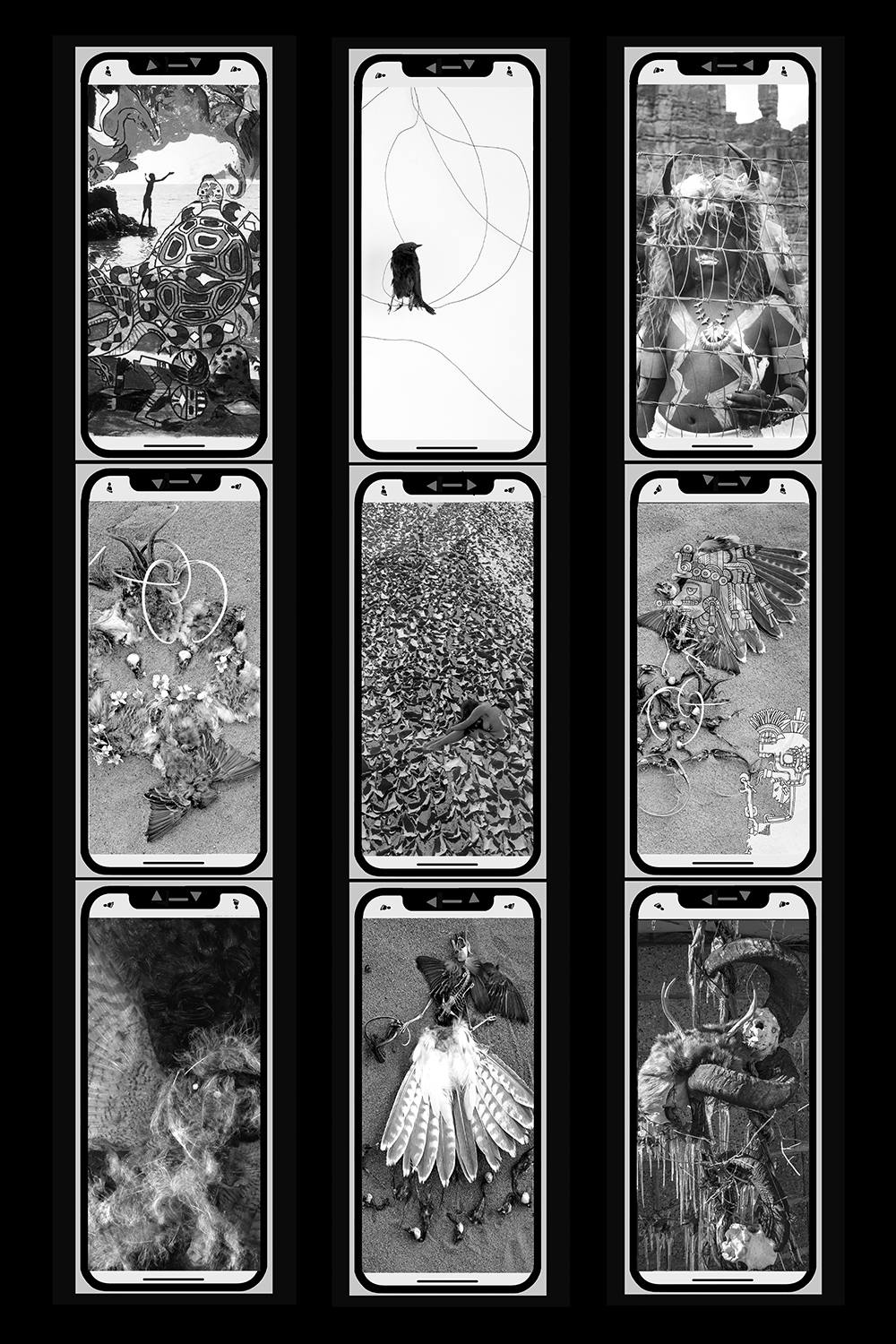

©Duwawisioma. Poquangt (Pookongt-twins Poqaung and Paloongaw-Echo), 2003

In the diptych Poquangt (Pookongt-twins Poqaung and Paloongaw-Echo) Masayesva has stacked iPhone portraits like twin communications towers to convey his concept of "twinness", symmetry, and balance. Conflict and chaos are a part of the duality conveying an overall impression of separate but equal. Harmony is sparked from the friction.

©Duwawisioma.Tipongyaveh, 2023

In the short video Tuuvutsi, he uses the photograph Tipongyaveh, which shows a village created from 35-millimeter slides and set in a cornfield, that is struck by an earthquake.

Within the exhibition are also a handful of typical older portraits made in Australia, Ecuador, India, and Hopi including a humorous self-portrait surrounded by cowboys and indians. The humor is tempered by hanging diabetes pill containers reflecting another aspect of the self-portrait.

As is part of Duwawisioma’s looking back he has re-seeded some of his earlier images, expanding the context from earlier narratives, as he matures. In the codex Navoti he combines an earlier 4-part narrative series Tuwapongya where he asked in this series in 1993, "We are given the ideal situation with the earth as an altar. The question is, how do you conduct yourself here?" Now Duwawisioma presents this as the beginning or end of an accordion-style codex where he has added menacing images from Kikmongwi’s Rain Songs (1979-1982) of floods, drought, disease, and the Red Owl (1993). Mounted back-to-back accordion style the new sequences go from positive to negative and negative to positive, oppositional forces related to each other. Being clear is knowing less and understanding more.

©Duwawisioma. Navoti, 1979-2023

The exhibition began with the remembrance of an uncle’s warning that not everything is what it appears to be, masked.

Duwawisioma creates digital collages from an amalgamation of stories, symbols, natural objects, and actual places. He brings to this body of work insights from the fields of biology, ecology, humanity, history, and planetary energy, along with concepts and traditions from the Hopi people. Rooted in Hopi cosmology, Duwawisioma explores an environmental and ontological reality meaningful to all people.

He has been awarded grants from the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, the National Endowment for the Arts, and the Arizona Commission on the Arts. He has been a guest artist and artist-in-residence at the School of the Art Institute of Chicago, the Walker Art Center, Minneapolis, MN, Banff Center for the Arts, Banff, Yamagata International Film Festival, Japan and Imagine Native, Toronto.

His photography, feature films, and short videos have been widely viewed including at the 1991 Whitney Biennial, the Native American Film and Video Festival, New York; The Museum of Modern Art, New York; Long Beach Museum of Art, California; World Wide Video Festival, The Hague; Whitney Museum of American Art Biennial, New York; Haus der Kulturen der Welt, Berlin; Pompidou Center, Paris, San Francisco Art Institute; Festival CineVideo de las Primeras Naciones Abya-Yala, Ecuador.