BEAUTY and DEATH in the ANTARCTIC Exhibition Dates: November 25, 2011 - January 31, 2012 |

December 14, 2011 is 100th anniversary of the first expeditions to reach the South Pole in the race between the Norwegian Roald Admanson who arrived on December 14, 1911, and the British explorer Robert Falcon Scott who reached it on Jan. 17, 1912. Scott's last diary entry was written on March 29, 1912. His body was found eight months later.

The Andrew Smith Gallery opens an exhibit of photographs marking the 100th Anniversary of the discovery of the South Pole in 1911. The Norwegian Roald Admanson and his party reached it first on December 14, 1911. Thirty-four days later on January 17, 1912 the British explorer Robert Falcon Scott and four men arrived. They had been traveling since November 1, 1911. On their return journey, Scott and his companions perished from cold and starvation. Scott's last journal was written on March 29, 1912. Andrew Smith Gallery presents a spectacular exhibit of historic and contemporary photographs of Antarctica by Herbert George Ponting (1870-1935) who was with Scott on his doomed Terra Nova expedition, and by the distinguished Santa Fe photographer Joan Myers who spent four months based at McMurdo Station as part of the National Science Foundation's 2002-2003 Antarctic Artists and Writers Program. The exhibit continues through January 31, 2012. Hurley also created a number of composite images consisting of substantial portions of painted detail added to photographed backgrounds. These were meant to provide a visual document of events in the expedition that he was unable to photograph, either due to lack of equipment or because circumstances made photographing impossible. HERBERT PONTING Herbert George Ponting was with Scott on the Terra Nova expedition to the Ross Sea and South Pole. He is regarded as the pioneer of modern polar photography in that he was the first person to combine the science of recording polar expeditions with fine art photography. He was also an early enthusiast of motion pictures having declared, “the fascination of a moving, living picture is irresistible -- the cinematograph is undoubtedly one of the greatest educators of the century.” The stunning photographs Ponting made during his 14 months with Scott at Cape Evans, Ross Island are formidable works of art that also encapsulate the "Heroic Age of Antarctic Exploration." Born in Salisbury, England in 1870, Ponting immigrated to California as a young man where he married and dabbled unsuccessfully in fruit farming and mining. By the early 1900s he had begun a new career as a serious free-lance photographer publishing in Camera arts magazines and was soon being hired by firms to cover newsworthy events. Like the British photographer Robert Fenton (1819-1869) before him, Ponting photographed in distant, turbulent regions. He reported on the Russo-Japanese war of 1904-05, and then traveled through Asia to Burma, Korea, Java, China, Japan and India, all the while selling his beautifully composed photographs to London's most respected magazines, periodicals, newspapers and publishers. Ponting documented scenery and events with an artistic eye, describing himself as a “camera artist.” He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Geographical Society. When Ponting joined Scott's Terra Nova team he became the first professional photographer to be employed on an Antarctic expedition. He described it as, “a chance, such as never would come to me again, to turn the experience that I had gained to some permanent benefit to geography, and that I was convinced that if I went, and were given a free hand to utilize my experience as I thought best, the photographic results might prove not only of great educational value, but a valuable asset to the enterprise.” (The Great White South, London, 1921). Before joining Scott and the crew in New Zealand for the voyage southward, Ponting quickly learned how to make movies. On sea and on land Ponting went to great, even risky lengths to get the photographs he wanted. He constructed various hoists to hold himself and his equipment over the edge of the ship to achieve a perfect shot. Crewmembers were requested to pose on the top of icebergs from which they sometimes fell and injured themselves. The men got used to 'ponting' (i.e. posing) for the camera which sometimes included tucking into Heinz baked beans and Fry's hot chocolate, products made by companies sponsoring the expedition. In early 1911 Ponting helped set up the winter camp at Cape Evans, Ross Island and built his darkroom. That winter he took flash photographs of Scott and his men inside their hut and made some of the first known color still photographs using autochrome plates. He was also one of the first people in Antarctica to use a portable movie camera called a cinematograph that took short video sequences. He photographed expedition scientists studying the behavior of large Antarctic animals like killer whales, seals and penguins. On one occasion, Ponting was nearly killed when a pod of eight killer whales almost knocked him and his camera off an ice floe into McMurdo Sound. After 14 months at Cape Evans Pointing and eight other men boarded the Terra Nova in February 1912 to return home since it had been determined they should leave before a second harsh winter set in. By then Ponting had complied more than 1,700 photographic plates of the Antarctic landscape and wildlife, as well as a narrative of the expedition. Before leaving Ponting photographed Scott and his men embarking for the South Pole on what everyone thought would be a successful journey. Expectations were that Scott would return a hero and that Ponting's cinematograph sequences, pieced out with magic lantern slides, would generate enough money to payback the expedition's massive debts. Instead, when the public learned that Scott in his last hours had written pleas to his countrymen to look after the welfare of the dead men's families donations poured in, enough to provide annuities to the living. The surplus was used to create the endowment of the Scott Polar Research Institute. Ponting spent the rest of his life lecturing, exhibiting and publishing his photographs and accounts of Antarctica. After World War I ended he published The Great White South, (1921) a book illustrated with 164 photographs and a narrative of the expedition. He also produced two films based on his surviving video sequences, The Great White Silence (1924 - silent) and Ninety Degrees South (1933 - sound). He lectured extensively on Antarctica until his death in London in 1935. His film The Great White Silence was restored by the British Film Institute and was re-released in 2011. Herbert Ponting was more than a freelance, professional photographer. His magnificent blue-green pigment carbon prints are among the finest examples of oversize pictorial photographs in the history of photography and were widely exhibited during his lifetime. Like Stieglitz, Steichen and Heinrich Kuhn, Ponting mastered the difficult and most spectacular of all photographic print techniques, the carbon process, which captured the dramatic nature of the Antarctic Midnight sun, the heroic nature of exploration, and man against nature as epitomized by the print "The Castle Berg, Scott's Last Expedition." Here the iceberg dwarfs the dog sled and man, and underlying it is the irony of Scott's failed mission, attributed by some to his improper use of dog teams.

HERBERT PONTING PHOTOGRAPHS

Centered beneath by a monumental, three-tiered iceberg, a man sits on a dog sled at the base of a massive sunlit formation rising hundreds of feet above him. Huge slabs of cracked ice wreathe the berg while on the far left snow covered mountains are faintly visible in the distance. Printed in rich green-black tones the large carbon print is a powerful composition of uncertain human endeavors in a savage landscape.

This oversize exhibition print is a study in dark and light textures that range from a swathe of mottled clouds veiling the sun, to the wave flecked ocean, the pock marked ice shelf, and the motionless black and white penguins in the foreground. In "The Midnight Sun" Antarctica's shifting elements have momentary quieted and a hush has settled over this beautifully composed landscape.

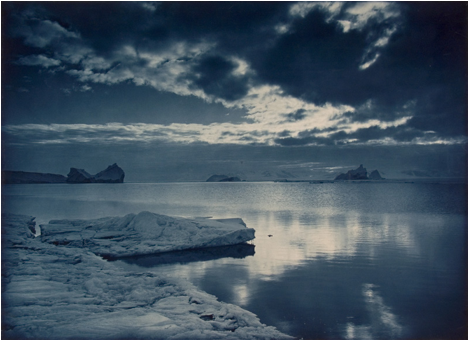

This magnificent oversize exhibition print captures the awesome reaches of Antarctica in a placid moment. Backlit clouds float over the unruffled ocean where several icebergs sail on the horizon. In the foreground a slab of ice recently broken off the coastline hangs over the water, tiny icicles hanging from its lip. The mood conveyed by this picture is of an immense, majestic solitude.

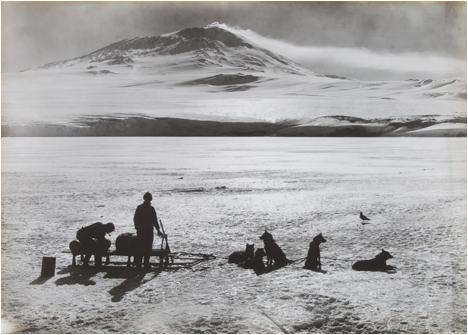

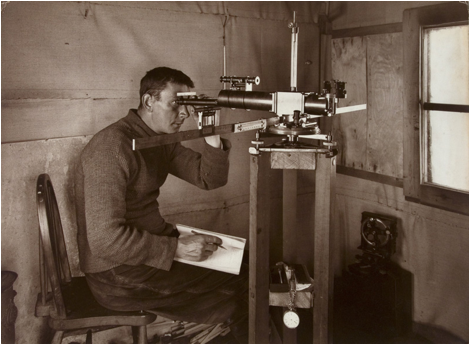

To make this photograph Ponting shot into the sun, silhouetting the two men, four dogs and a solitary bird against a shining expanse of ice below Mount Erebus. From the volcano cone misty steam forms a contrail over the mountain slope. One of the men gazes at the volcano while the other, pipe in mouth, bends over a bag on the dog sled.  "Dr. Simpson" Negative Date: 1910-12 ca. Print Date: 1910-12 ca. 13.125" x 18" Carbon Print HGP/1009 The imminent meteorologist Dr. George Simpson (1878-1965) was photographed aboard the Terra Nova taking notes as he peers through a telescopic apparatus attached to a wooden platform. A small stove is just visible in the tight quarters. Dr. Simpson was a specialist in atmospheric electricity and the first person to lecture in meteorology at a British university (Manchester University). He had worked in many of the meteorological stations in India and Burma before joining Scott's Terra Nova expedition. In Antarctica he constructed one of the continent's first weather stations and conducted balloon experiments to determine how altitude affects temperature. After Scott's death Simpson went on to have an illustrious career in the fields of atmospheric electricity, ionization, radioactivity, lighting, and solar radiation. He was knighted in 1935 and lived until 1965. JOAN MYERS New Mexico photographer Joan Myers is one of the most intelligent and prolific artists working in tradition of exploration/travel photography. Over the last thirty years she has produced photographic projects and books about the Santa Fe Trail, Japanese relocation camps, images of older women, the pilgrimage route to Santiago de Compostela in northern Spain, the environment of the Salton Sea near Palm Springs, California, Antarctica, and most recently, geothermal sites around the world. Long fascinated with the South Pole, Myers was chosen by the National Science Foundation to participate in their 2002-2003 Antarctic Artists and Writers Program. She spent four months based at McMurdo Station photographing virtually every aspect of the place, which she documented in her book "Wondrous Cold: An Antarctic Journey" (2006). Robert Falcon Scott, Ernest Shackleton and Herbert Ponting's legacies were of particular interest and she made many photographs of their camps. Away from McMurdo Myers experienced a terrain little changed since the time of the early explorers. Temperatures were often subzero with wind chills as low as -60 degrees. Simply keeping her fingers warm enough to operate her camera equipment was one of many challenges she faced daily. JOAN MYERS PHOTOGRAPHS SHACKLETON'S HUT Robert Falcon Scott led two polar expeditions to Antarctica. On his first Discovery expedition of 1901 - 1904 he was accompanied by Ernest Henry Shackleton as his third officer. Shackleton was sent home early for health reasons, but he returned to Antarctica throughout the course of his life to lead or accompany expeditions. On his "Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition of 1914-17 his ship the Endurance was trapped in pack ice and slowly crushed, yet Shackleton survived this and other disasters. His daring feats of exploration and survival earned him a knighthood. In 1921 when he was 47 year old Shackleton returned to South Georgia, Antarctica where he died suddenly of a heart attack. His body was buried there. Myers photographed Shackleton's hut at Cape Royds that the men of the Nimrod expedition built in 1908 and inhabited with 15 men living and working in the 33 by 19 by 8 foot hut. She photographed the hut half buried in snow and its contents; cooking utensils, ancient biscuits, bottled currants, tea, fish and meats. Shoes neatly stowed under bunks and a large cast iron stove topped with tea kettles give the impression the men have just stepped out. DISCOVERY HUT On November 2, 1902, Scott, along with Shackleton and Edward Wilson made their first attempt to reach the South Pole. They were part of the 1901-1904 Discovery expedition and had been based at Hut Point, (today a short walk from McMurdo). Their effort was unsuccessful, but it marked the beginning of the race between them and Roald Amundsen. Scott's men constructed the 37 x 37 foot hut from jarrah wood and used it primarily for storage. Myers photographed the Discovery Hut from the outside with Observation Hill in the distance, a steep volcanic mountain that Scott's men climbed for exercise. Inside she photographed an old primus stove and a skillet full of blubber set out by the explorers. An especially powerful image is her photograph of a window to the outside whose light is nearly extinguished under layers of snow and icicles.

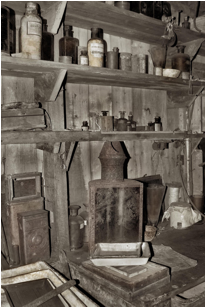

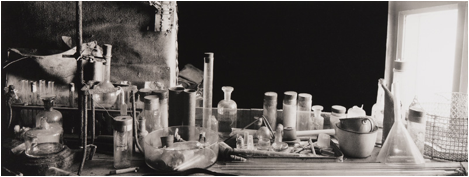

SCOTT'S HUT Myers made numerous photographs of Scott's Hut under Wind Vane Hill at Cape Evans where Scott, Ponting and the others lived and wintered over before the doomed trip to the Pole. British explorers intentionally left behind anything they did not need for the benefit of others who might come after them and indeed the supplies left in Scott's hut later saved Shackleton's men who had lost most of their provisions when their boat broke anchor and drifted out to sea. Shacketon's Ross Sea party used this hut in 1915-17 while they were laying depots, unaware that their ship the Endurance was being crushed by ice. Myers had to abide by strict rules that nothing in the hut could be touched. She had to photograph in near darkness, though her digital camera had no difficulty making exposures. "To peer into the hut's darkness is to see time frozen," she writes in "Wondrous Cold: An Antarctic Journey." She took pictures of Ponting's makeshift darkroom where bottles of chemicals and glass beakers still line the original wooden shelves. She writes: "In his account of Scott's 1910-12 Terra Nova expedition, The Great White South, Herbert Ponting describes how he built his own darkroom at the east end of the hut. Its size, some eight feet long, six feet wide, and eight feet high, indicates the importance of photography to the expedition. He framed walls and covered them with rubberoid to make them light and watertight. He also built storage shelves and a bed that folded down for sleeping. When he closed the darkroom door to develop film the temperature in the unheated space would rapidly fall, and once a week he would have to chip a mass of ice formed by condensation off the walls." In one of Myers's photographs we see a shovel still topped with ancient snow with the words "British Antarctic" stenciled on the boards behind it. "There's something both eerie and awesome about seeing the quotidian marks of men who lived here almost a century ago," writes Myers. "You enter the hut via a small hallway where snow shovels and other outside tools are hung. Beyond the entryway are piles of seal blubber, perfectly preserved, and the pony stables, lined with bales of hay. Inside, along the walls of the living area, are open cubicles with sleeping bunks, Scott's little den, and Captain Oates's bunk draped with harnesses and snowshoes for the expedition ponies he was hired to handle. A frozen emperor penguin lies on the table ready for dissection by Dr. Edward Wilson, scientist and artist."

Other photographs include the Geographic South Pole with a flag flapping in the wind, a blizzard sweeping over Cape Evans, turquoise colored icebergs, and innumerable penguins. Frank Hurley (1885-1962) was born at Glebe, Sydney, the second son of a Lancashire-born printer and trade union official and his French wife. He ran away from home at 13, worked in the steel mills at Lithgow and two years later returned home to study at the local technical school and attend science lectures at the University of Sydney. The young man bought a Kodak box camera and taught himself how to make photographs. By 1905 he was working in a Sydney postcard business where he gained a reputation for the quality of his work and the extraordinary risks he took to get sensational images, such as photographing an oncoming train. By 1910 he was lecturing and exhibiting his photographs in Sydney. On January 1, 1914 Ernest Shackleton, confident of enough financial support, announced plans for his Trans-Antarctic Expedition. From the nearly 5,000 applications he received from people eager to join the crew Shackleton picked 56 men. The Endurance sailed from London on August 1, 1914, a few days after World War I had been declared. Shackleton volunteered to put his ship and crew at the deposal of the war effort but both the King and Winston Churchill instructed him to proceed to Antarctica. The expedition reached Buenos Ayres on Oct. 26 where photographer Frank Hurley joined the crew bound for South Georgia, the southernmost outpost of the British Empire. Hurley had already made two trips to Antarctica before hooking up with Shackleton's expedition and had proved to be tireless and enthusiastic under the most challenging circumstances. Although only in his mid-twenties he had been hired as the film and movie photographer for the 1911 Australasian Antarctic Expedition. From there he had traveled to Java, made a second trip to Antarctica, and worked on a filming expedition through northern Australia before joining Shackleton's expedition. On route to South Georgia Hurley rigged a platform under the jibbom so that he could take kinematograph (motion) pictures of the first icebergs sighted and of the ship's prow breaking through ice. The Endurance was a new vessel, one of two ships selected for the expedition. It had been built in Norway, constructed specially for the Polar environment, and was loaded with oil fuel as well as coal to enable her to stay out to sea longer. Hurley turned out to be a useful member of the crew even beyond his skills as a photographer. He was in charge of one of the dog teams and was ingenious at jerry-rigging equipment. According to Shackleton's memoir: " . . . Hurley, our handy man, installed our small electric-lighting plant and placed lights for occasional use in the observatory, the meteorological station, and various other points. We could not afford to use the electric lamps freely. Hurley also rigged two powerful lights on poles projecting from the ship to port and starboard. These lamps would illuminate the "dogloos" brilliantly on the darkest winter's day and would be invaluable in the event of the floe breaking during the dark days of winter. We could imagine what it would mean to get fifty dogs aboard without lights while the floe was breaking and rafting under our feet." Hurley's most famous still photographs show the Endurance being slowly crushed by pack-ice and the crew camped out on the ice floes struggling to stay alive. As the ship was breaking up Shackleton wrote: "Hurley meanwhile had rigged his kinematograph-camera and was getting pictures of the Endurance in her death-throes. While he was engaged thus, the ice, driving against the standing rigging and the fore-, main-, and mizzen-masts, snapped the shrouds. The foretop and t-gallant-mast came down with a run and hung in wreckage on the fore-mast, with the fore-yard vertical. The main-mast followed immediately, snapping off about 10 ft. above the main deck. The crow's nest fell within 10 ft. of where Hurley stood turning the handle of his camera, but he did not stop the machine, and so secured a unique, though sad, picture." After the Endurance sank the crew dragged their boats miles over the unstable ice toward open water. After numerous adventures they embarked through the "lanes" of ice for Elephant Island, a harrowing journey that took five days. Hurley had devised a pump made from the bar case of the ship's standard compass, which was quite effective, though its capacity was not large. Miraculously, the small, weather beaten boats withstood the worst storm-swept waters in the world to reach Elephant Island where the men, nearly dead from exposure and hunger, set up camp. Even at this stage of the journey Hurley, tough as nails, did not stop taking photographs. As Shackleton writes: "When the James Caird was afloat in the surf she nearly capsized among the rocks before we could get her clear, and Vincent and the carpenter, who were on deck, were thrown into the water. This was really bad luck, for the two men would have small chance of drying their clothes after we had got under way. Hurley, who had the eye of the professional photographer for "incidents," secured a picture of the upset, and I firmly believe that he would have liked the two unfortunate men to remain in the water until he could get a "snap" at close quarters; but we hauled them out immediately, regardless of his feelings." The remainder of Shackleton's epic journey and his superhuman efforts to rescue his men from Elephant Island is legendary. At the end of their nearly two year ordeal not a single man had died and all returned home to a hero's welcome, although their stories were quickly eclipsed by the larger drama of World War I. By 1916 Hurley was in London assembling his photographs and film of the expedition. The following year he returned to South Georgia to finish his movie, "In the Grip of Polar Ice." In 1917 he joined the Australian Imperial Force as an honorary captain and official photographer and again took great risks to photograph battlefields. At the Third Battle of Ypres he recorded the violence and carnage, describing it as 'a weird and wonderful sight, with the destruction wildly beautiful'. Despite the power of his war photographs army administrators tried to censor his creative use of composite pictures to achieve something larger than a single negative could offer, accusing him of being "little short of fake." Angrily, Hurley resigned his post, but was sent to the Middle East where he continued to photograph battles. In Cairo he met a young opera singer, Antoinette Rosalind Leighton, the daughter of an Indian Army officer, and after a ten day courtship married her. Throughout his career Hurley made documentary as well as dramatic feature films and worked as a cinematographer for Cinesound Productions. His films and books were major commercial successes, in part because he loved creating sensational stories, even if this did not always sit well with his critics. He was awarded the Polar Medal and two bars and in 1941 was appointed O.B.E. During World War II Hurley was sent back to the Middle East as the official photographer with the Australian Imperial Force. He continued to make documentary films for the British government until 1946, although by then a generation of younger film makers found his meticulous method of working old fashioned and eccentric. Back in Australia Hurley devoted the rest of his life to still photography, lecturing and publishing photography books of Australian lands and cityscapes. He died in his home on January 16, 1962. A.F. Pike says of him: "Frank Hurley was always restless, a self-styled loner who braved danger in exotic areas to provide romance and adventure for armchair travelers. He retained the use of 'Captain', to help cultivate this image. For three decades he inspired Australian film makers and photographers and was the most powerful force to shape Australian documentary film before World War II."

Liz Kay

|